I learned a lot about books — more than I’d meant to — while preparing a blog post last month. It’s a personal story, full of real highs and some real frustrations, and a few moments of honest-to-god history. And it all ends up with a picture of a little boy waving at a train…

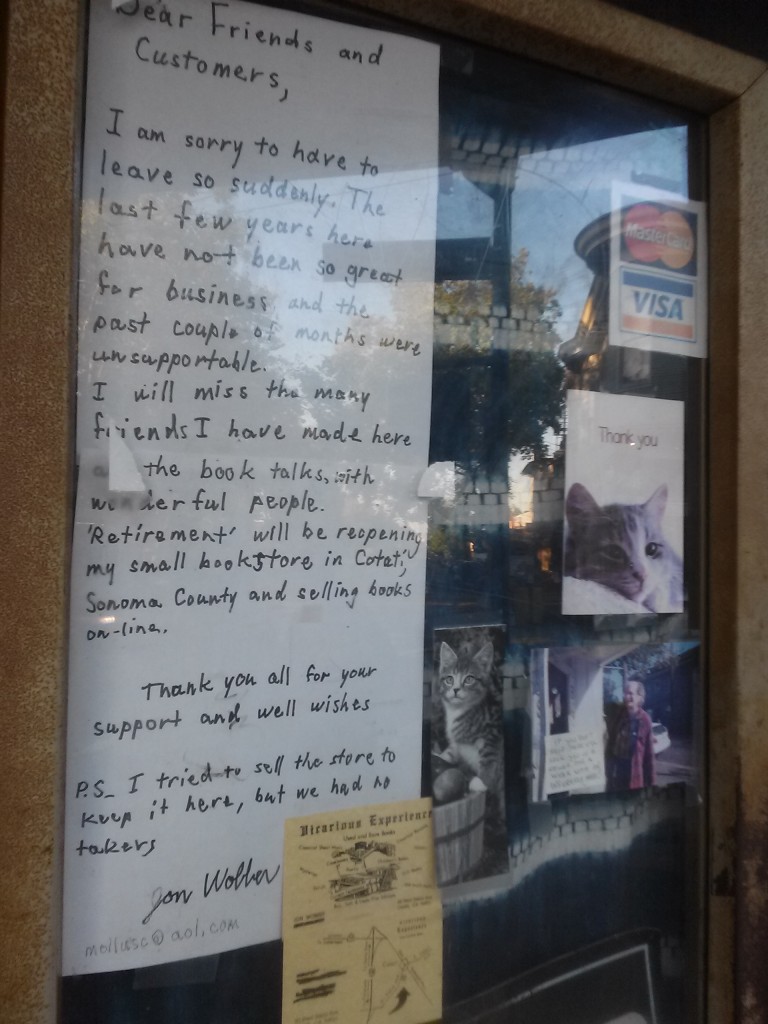

I was thrilled when my book club finally agreed to read one of my all-time favorite novels. But could I still find a hardcover version of the original 1943 novel? By the end of that evening, I’d visited six different bookstores, and only one of them had a copy on their shelves. But even more startling, I discovered that two of my favorite bookstores had gone out of business!

|

Closed Nothing by the Author… Only one obscure book by the author… Out of business Had the book! Out of business |

After 50 years, Berkeley’s “Shakespeare & Co.” closed in June of 2015

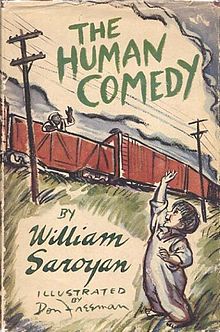

In the end, it was easier to just purchase the book on Amazon — especially since I was able to locate both editions. (The revised 1966 Dell paperback, and the original Harcourt Brace and Co. hardcover from 1943). And I was delighted that I’d even found a version with the original dust jacket… William Saroyan had won a Pulitzer Prize just three years before he wrote The Human Comedy. So it felt tragic that it was so difficult to find a bookstore that would sell me a copy — and very important that I pursue this to wherever it led…

I’d live with these books for the next month, revisiting its story of small-town America — and discovering all the startling differences between the original and revised editions. And the very first difference I discovered was pretty substantial — every chapter’s title had been changed. “All the World Will Be Jealous of Me” had become simply “At Home”, and “You Go Your Way, I’ll Go Mine” had become “Mrs. Sandoval.” Soon I was stunned to discover that that pattern was repeating for every single chapter, which suggested more rich details that might be slipping away…

| A Song For Mr. Grogan | Mr. Grogan |

| If a Message Comes | Mrs. Macauley |

| Be Present at Our Table, Lord | Bess and Mary |

| Rabbits Around Here Somewhere | The Veteran |

| The Two-Twenty Low Hurdle Race | Miss Hicks |

| The Trap, My God, the Trap! | Big Chris |

| I’ll Take You Home Again | Going Home |

| Mr. Grogan on the War | The Telegram |

| To Mother, with Love | Alan |

| It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own | After the Movie |

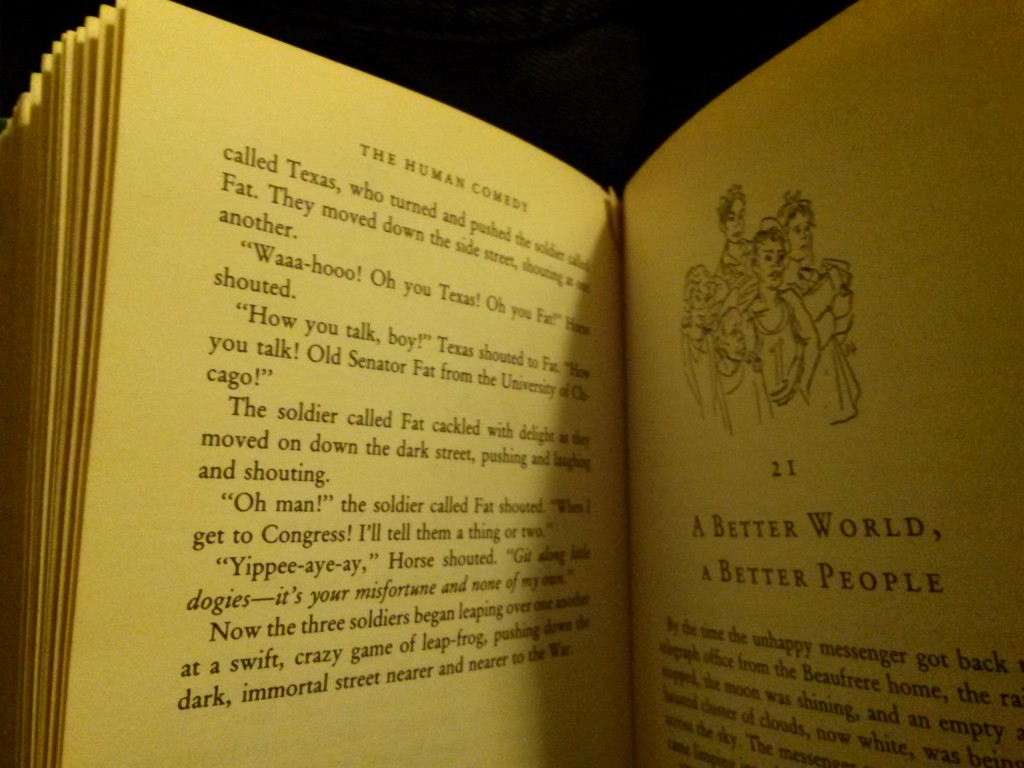

| A Better World, a Better People | Valley Champion for Kids |

| Let There Be Light | The Holdup Man |

| Death, Don’t Go To Ithaca | The Nightmare |

| Be Happy! Be Happy! | Mr. Ara |

| There Will Always Be Pain in Things | Mrs. Macauley |

| All The Wonderful Mistakes | Lionel |

| Leaning on the Everlasting Arms | On the Train |

| A Letter from Marcus to His Brother Homer | Marcus |

| Here is a Kiss | At the Church |

| The Trees and the Vines | Spangler |

| Ithaca, My Ithaca! | Ithaca |

| Love Is Immortal, Hate Dies Every Minute | The Horseshoe Pitchers |

| The End and the Beginning | The House |

Wait a minute — there’s two different chapters that are both named “Mrs. Macauley.” (See what happens when you name chapters after their primary character?) It was fun exploring the book for its changes, both big and small, and the second difference I discovered was just one word in the first chapter. But it still seemed like it was a pretty important change…

The little boy turned slowly and started for home. As he moved, he still listened to the passing of the train…and the joyous words: “Going home, boy — going back where I belong!” He stopped to think of all this, loitering beside a china-ball tree and kicking at the yellow, smelly, fallen fruit of it. After a moment he smiled the smile of the Macauley people — the gentle, wise, secret smile which said Yes to all things.

In the revised edition, “Yes” was changed to “Hello”.

I even discovered a new typo that was introduced in the revised edition. (Unless “indredible” is a word.) But more importantly, in chapter three, they’ve trimmed the conversation where the manager of the telegraph office asks his 14-year-old messenger about what future he’s mapped out for himself. “Well… I don’t know for sure, but I guess I’d like to be somebody some day. Maybe a composer or somebody like that — some day.”

“That’s fine,” Spangler said, “and this is the place to start. Music all around you — real music — straight from the world — straight from the hearts of people. Hear those telegraph keys? Beautiful music.”

“Yes sir,” Homer said.

In the revised edition, the conversation goes like this.

“Well… I don’t know for sure, but I guess I’d like to be somebody some day.”

“You will be,” Spangler said.

I wondered if the author was trying to shorten the book — to make it more like a paperback, for mass-market consumption. (The sentence “You know where Chatterton’s bakery is?” was changed to “Know where Chatterton’s bakery is?”) It’s like watching deleted scenes from a movie. Sometimes you sense that it made the movie shorter, but at the same time it’s also eliminated some context.

An entire chunk of dialogue was cut from the end of the scene at the telegraph office.

“Mr. Grogan went on, his mouth full of cocoanut cream. ‘Do you feel this world is going to be a better place after the War?’

Homer thought for a moment and then said, ‘Yes, sir.’

‘Do you like cocoanut cream?’ Mr. Grogan said.

‘Yes, sir,’ Homer said.

Are these significant changes? If a story’s strength lies in its poignancy, then how do you measure the value of dialogue? Here’s some more sentences that were edited out of chapter 4, when the smallest boy wanders into a conversation with his mother and older sister, asking about the brother who’s gone away to war.

“Where’s Marcus?”

Mrs. Macauley looked at he boy.

“You must try to understand,” she began to say, then stopped.

Ulysses tried to understand but didn’t know just what was to be understood.

“Understand what?” he said.

“Marcus,” Mrs. Macauley said, “has gone away from Ithaca.”

“Why?” Ulysses said.

“Marcus is in the Army,” Mrs. Macauley said.

In the revised edition, that scene was shortened to simply two sentences.

“Where’s Marcus?”

“Marcus is in the Army,” Mrs. Macauley said.