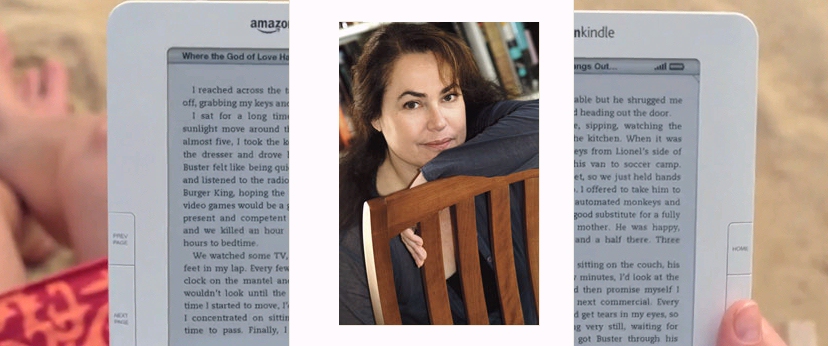

Amy Bloom was the first author to discover that her book was appearing in a Kindle ad. But I was actually a little disappointed when I’d interviewed her last summer. I’d thought she’d be more excited about it!

Q: Did you get any other reactions from people you know?

AMY: Another friend of mine said, “Hey, guess what?”

You know? “I fleetingly saw your page in a Kindle ad!” And that was nice. You know, I’m the dullest person in the world. I say, “Oh, that’s so nice.” And they go, “Yep.”

Q: I guess I was expecting you’d have a bigger reaction to the ads.

AMY: I am notorious for this in my family. I’m pleased by them. I’m flattered by them, but I don’t – they’re not – they’re great. I’m really appreciative and I think its very kind of the Kindle people. I feel very grateful for whoever it was who said, “Hey, how about a page from an Amy Bloom story.” I feel very grateful for whoever that person is.

Q: Will this increase sales of your book?

AMY: You never know. It probably won’t do me any harm.

On the other hand, the other way to look at it is, who cares? I’ve done my job as a writer. I’ve written the best work I know how. And I’m appreciative of the people who read it and care about the work — and that’s pretty much the end of that. Anything else that happens is sometimes nice, and sometimes not so nice, but not really directly relevant…. I think it’s — I am really appreciative, and it’s also sort of in the category of ephemera.

Q:But is there a larger significance?

AMY: If there is a larger significance, it’s going to be someone else who figures out what it is, not me.

Even though she doesn’t own a Kindle herself, she said she was glad that people were reading, saying “it doesn’t matter to me whether people read wax tablets or printed books or handmade books or ebooks. I’m happy that they read!” (And she added, graciously, that “I’m sure when I’m a little old lady, I’m going to be very grateful to have some lightweight thing that contains a lot of books and has big fonts…”) But it was exciting to see her commitment to the craft of writing, and I realized that we both had something in common: a deep love of fiction.

That’s why I was especially delighted when I discovered Amazon had just published a personal “Letter from Amy Bloom” on the web page for one of her books. In it, she describes her philosophy about fiction — offers an insider’s perspective on why it’s so challenging!

The great pleasure for me in writing short stories is the fierce, elegant challenge. Writing short stories requires Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart, and some help from Gregory Hines. We are the cat burglars of the business: in and out in a relatively short time, quietly dressed (not for us the grand gaudiness of 600 pages and a riff on our favorite kind of breakfast cereal) to accomplish something shocking — and lasting — without throwing around the furniture.Flannery O’Connor (a reliable source when appreciating the short story) wrote that short stories deliver “the experience of surprise.†The surprise, I think, is that so few pages can contain so much, that what is taken to be a prism turns out to be not only a window but a door as well.

If you’re an American reader, you can love short stories the way other Americans love baseball; this is our game, people! We have more than two hundred years of know-how and knack, of creativity. Of the folksy and the hip, of traditional yarn-spinning and innovative flourishes. Of men and women, of war and loss and love, with a few ghosts and many roads not taken. And in all of that, you will find some of the funniest and most heartbreaking fiction, ever.